Changing Lanes

by Mimi Schwartz | Just keep swimming.

“Why don’t they fix the window?” I almost asked when I started coming to this pool, part of Princeton University. It was 6:30 a.m., right after New Year’s Day, and the place was packed with the before-work crowd. The window, fifteen feet above my head, was wide open and snow was falling on the locker room floor. (No Berber carpet like at the YMCA, no sauna or built-in hair dryers either.) But the two coeds who were changing clothes on either side of me—young, flat-bellied, and high-bosomed—seemed unconcerned, so I kept my mouth shut, changed quickly. If that’s what it takes, post-forty, to get in shape at a high-powered pool, so be it.

~~~

Ten years later the window is still open and it’s still freezing; but today, at mid-morning, no one is here. I hurry to get my suit on before someone from the lunch-time crowd comes. That’s silly, the poet Audre Lorde would say, there’s nothing to hide. She wouldn’t wear a prosthesis after her mastectomy, she says in The Cancer Journals, even when the nurse in her doctor’s office complained that it set a bad example.

But I was never one to parade around. Even without this scar across my chest—it’s still so red—I was never like those fleshy, German women at the pool in Barcelona last summer, cavorting around with bare breasts and bellies bulging out of G-strings. No American woman around here over size 10 would dare. (Not that I’m not size 10 anymore.)

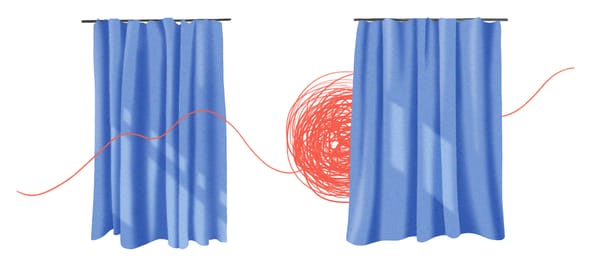

Lanes four and five, which in early morning share a dozen Speedo suits moving like torpedoes, now have two sprinters; lane three, my old lane, has no one. I stay away, still remembering that guy—was it two years ago?—who passed me and snarled, “Why don’t you swim lane two, lady?” He was doing the breaststroke and I was doing the crawl, my fastest stroke. True, a few people had already passed me, but after him everyone went by, and a week later someone kicked me in the head. So I switched to lane two, crushed. Wasn’t I the fastest swimmer in bunk ten of Camp Inawood, with trophies somewhere in the basement to prove it? Now I’ll overtake everyone, I thought, swimming leisurely—until a guy who didn’t look like much, stroke-wise, overtook me in lane two. An old, heavyset woman almost did, but I speeded up.

~~~

This morning I’m swimming in lane one—just temporarily, of course, until I get my left arm back in shape. My surgeon said three weeks at most, if I keep doing walk-the-wall exercises and start to swim again. And the oncologist called to say no lymph nodes were involved, so no chemo is needed. Just a pill, tamoxifen, once a day, which I started this morning. No problem.

I sit on the rim for a while, dangling my feet, my towel around my neck to cover the slight cave-in where my bathing suit begins. I sit straighter, looking at the cold water. Even before, I hated getting in; it was getting out I liked—doing thirty-six laps in thirty minutes, forty laps on good days. But not today. I’ll try for six laps, maybe.

In the water before me a huge, bald-headed old man, he must weigh over three-hundred pounds, is moving like a dead whale. How can someone be so relaxed with a butt rising every few strokes like Moby Dick? In front of him a thin-haired woman in giant goggles is doing the doggie paddle. She is working so hard trying to keep her head above water. A young woman at the far end is floating on her back. I wonder why she’s here at this hour; she must be my daughter’s age.

No one in this lane seems to care about the clock. How can they go back and forth so aimlessly? Annoyed, I slip in to join them. I start slow, concentrating on my arm, and feel it stretch five, ten, twenty times across the pool. I forget about gliding gracefully like Esther Williams in old movies on AMC and try to find a comfortable position. One, two, one, two. The scar doesn’t throb.

~~~

My friend Rhoda told me that she is getting fat, and so what? She is tired of eating diet salad dressing and ice milk and wants the real thing from now on. And my cousin Joanne has announced that she is letting her hair turn gray. One, two, one, two. She doesn’t care if she finds someone new. “Don’t be dumb!” I told them both with the optimism they expect from me, “You’re young if you keep in shape. It’s letting go that makes you old.” One, two, one, two ...

Maybe letting go isn’t bad. I picture myself sinking to the chipped tile floor twenty feet below, but I float upward, surprising myself. One, two, one, two … My shoulders relax, and I ease into a rhythm of forgetting, which, over the coming years, will carry me forward into new possibilities. Eleven years from now, I’ll prefer a wide lake in summer, how I can swim with no constraints into early morning mists, the rising sun on my back, the loons calling from somewhere. But for now I’m happy to fix, as always, on the solid black line painted on the pool floor. One, two, one, two … I’ll be fine, fine, One, two, one … until someone touches my foot. Damn, even in lane one! I speed up again, losing track of my count, and pull into an open stretch without looking back to see who it is.

Mimi Schwartz is the author of seven books, most recently Good Neighbors, Bad Times Revisited: New Echoes of My Father’s German Village (2021); When History Is Personal (2018); and Writing True: The Art and Craft of Creative Nonfiction (2013), with Sondra Perl. Her short work has appeared in the Boston Globe, Ploughshares, the New York Times, Tikkun, Creative Nonfiction, Pangyrus, River Teeth, and the Writer’s Chronicle, among others. She is professor emerita in writing at Stockton University and lives in Princeton, New Jersey. More at: mimischwartz.net

This essay originally appeared in Fourth Genre #3.1 (2001).

Support our efforts: ☕ buy us a coffee.