notes from the underground

by Melissa Matthewson | Start with the word.

start with the word catholic and an image surfaces—what first? Brother Aquinas adorned in black robes, his large gold cross (or was it silver) swinging hip-to-hip, his cloaked arms holding tight the Bible to his chest, in reach of his heart. Never a novel, as in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which we read together in those subdued periods after lunch: I shall express myself as I am. I will not serve that in which I no longer believe. He assumed a wry smile, knowing something I did not, nodding to me gently as he passed the school’s lawned grotto with Mother Mary balanced on the brick stones, the stations of the cross headlining the campus green. Now, when I run my finger along the thesaurus entry, I cut to the shared synonyms—catholic, see also: tolerant, cosmic, liberal, broad. Latitude, even. Is that not freedom?

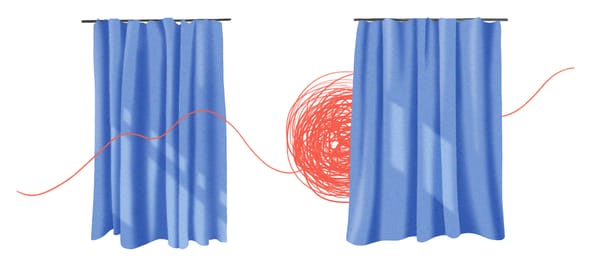

start with the word speech, of utterances, of expression. As in this story: It’s 1990 and I’m thirteen, awkward and fiercely devoted to Walt Whitman and Kirk Cameron both. Pop culture and poetry, side-by-side. It’s 1990 and I’m waiting for something to happen, anything, reading the news: Nelson Mandela walks free, touching his prisoned feet to the country of brown earth, in exaltation, in grief; elsewhere in Manchester, England, inmates riot, closed up and bolted into the prison chapel, spreading out to the pews, the contrast of their orange garments sharp against fine wood, for what: freedom. I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can. I begin to write short essays on private school, plaid uniforms, adolescent rage, compile them into an illegal newspaper distributed at lunchtime on the quiet lawn, the noon light stripping the trees into corrugated shadows, all that stunning bougainvillea and Ceanothus murmuring with spring. I type out the words with my friend K in her dark bedroom, the suburbs quietly massacring the orange groves out the window, this friend K who introduced me to Virginia Woolf and revolution, whose Vietnamese grandmother was so beautiful, so small, cooking stews all afternoon and drinking foreign teas from tiny cups. The rose garden out back alive with thorns and bees and any number of wild shrub or insect. We call it the Underground Pravda, so named after a Soviet paper. My father copies the tabloid on Sunday at his EF Hutton office, the desks empty of brokers and agents for now, the still air of the economy on the precipice of waking up to a new stock day. Read: Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech.

start with the word private, then add school, then the Sisters of the Company of Mary, Our Lady, an order whose mission unfolds its history like a straight bar from the slopes of Bordeaux, all the spokes of their vocation pointed toward the individuation of a girl. And that’s a fact until you add the thinking mind and all its impulse and intellect. I am not afraid to make a mistake, even a great mistake. Add to the curriculum my English teacher, Mr. Rewald, who said the word dissent, who storied the afternoon with nature versus nurture and the wild call of wolves and bad men who beat their animals into submission, who reminded me that those trees out there are fierce with the possibility of beauty, who said power in art, who said write a line that lessens the distance between us, filling the lonely gaps with stories too many to count.

start with expel and continue with tyranny of the school government and the disapproval of the rector, whose only fame was a Hollywood actress for a niece and a stance tall and mean. Start with severity, of a rule system not devised for fracturing by the design of two young girls who only set out to create something unique and individual. Who only wanted to write: remake the ordinary of daily life into something beautiful, structure their imaginations, maybe grow them, just a bit different from the other students. No, rules are rules, contrived not to be broken. In the wide land under a tender lucid evening sky, a cloud drifting westward amid a pale green sea of heaven, they stood together, children that had erred. All this, followed by a final goodbye from the lit teacher, who requested a meeting in the empty classroom, the room now curved into a posture of disappointment, its chairs formed into an open build so that discourse grew from its shape—a blueprint for making eye contact and speaking history under rotating fans instead of backs set up for divine rectitude. All this, followed by the hammering of the Constitution by my father, advocating for rights and justice, for freedom, that word so related to—

catholic.

end with the antonym, which is narrow. Limited. Insufficient. Still, this doesn’t parse: how to understand a word so separated from its common usage in the context of this story, so paradoxical, so contrary. Instead, shove the word out entirely, or go back to its origin from the Greek, katholikos, and say, this is what we desire as universal: a vision of art both progressive and true, of open craft and limitless words, outside of institution, outside of rule.

Melissa Matthewson is the author of Tracing the Desire Line from Split/Lip Press (2019). Her nonfiction has appeared in Guernica, Aeon, Literary Hub, the Rumpus, Oregon Humanities, Longreads, Mid-American Review, Bellingham Review, River Teeth, Terrain.org, American Literary Review, and Catapult, among other publications. She writes for Southern Oregon University and teaches in the low-residency MFA in Creative Writing program at Eastern Oregon University. Find her at melissamatthewson.com or on Instagram @mazzymaple.

This essay originally appeared in Hobart (October 2016) and appears in Tracing the Desire Line.

New here? Every issue of Short Reads is available on our website.