The Annual Bonfire, 1998

by Lynette D’Amico | Secrets in the smoke.

—Lincoln Journal Star, Dec. 9, 2017

In September, the hungry ghosts emerge from hell to stretch their skinny legs. Their joints clack together like dry wood, and their throats are blocked by knots.

The last Saturday of September, we hosted a bonfire. This was in rural western Wisconsin, when I lived with M.

In September, the light thinned. Oak leaves were purple and brown. Sumac leaves blazed red in late summer. The buckeye leaves jump-started fall and turned yellow all at once, all on the same day. The leaves dropped the same way, not one at a time, but again, all at once, as if a string connecting the leaves had been pulled.

The ghosts’ hunger was the hunger of secrets and regrets. Maybe no one held their hands at death; no one washed their cooling bodies or sang to them.

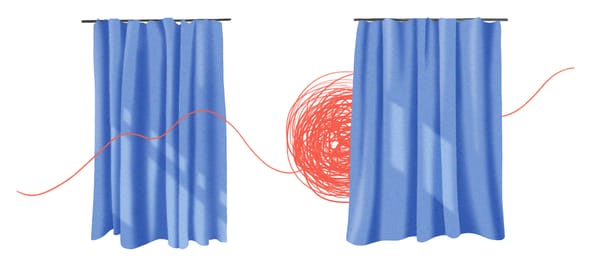

Trees don’t really turn colors, you know. In fall, the green pigment stops being produced and other colors are revealed, like a secret you always knew.

The fire was a tradition—the second annual bonfire, the fifth, the eighth—and then, when M. and I were over, it was over.

~~~

At dusk, as bands of pink and purple stretched across the sky, we lit the bonfire. We invited guests to contribute to the burning. What would you want to reduce to ash? Old love letters? Time sheets from a despised job? After the knee injury that short-circuited Mello’s fast-pitch softball career, she burned the X-rays in the bonfire. The fire was as forgiving as a confessional, as redemptive as live water.

These were M.’s old bar friends, the crowd sliding down the slack side of middle age, so many now dead or close to the end years. They roasted hot dogs on long willow sticks, the flames still blazing. The hot dogs crisped to ash, the willow branches burned like torches. They dripped mustard down their sweatshirts, tripped over open cans of beer, smoked and coughed and smoked.

Dot Kittleson wrapped herself in a sleeping bag, her thick legs propped on a cooler. She had worked at ADM Milling moving pallets of fifty-pound bags of flour in and out of railcars for twenty-two years and never lived with a lover. In a bar fight her spleen had been pierced by a nail file. Nobody had seen the scar, but looking at her you’d believe it was there. She walked like an old broken-down rodeo rider, listing from side to side, her arms hanging like dumb animals at her knees.

Tee Jae Montgomery was there, lighting the cigarettes of her latest lover, who looked sharp in a velvet beret. Jane was married and still lived with her husband, who didn’t know about his wife’s secret.

Some of those hard women, with their hard, square bodies, smoking cigarettes, pounding shots, had two names: a gay name and a straight name. Kooks was also Kathy. Sadie was Karen. I never knew Mello’s straight name—just that she pitched for the Minneapolis Avantis and was inducted into the Minnesota ASBA Hall of Fame in 1989.

When I asked the women with two names for their latest addresses, they shrugged and changed the subject. Thanks for the Christmas card, they said, but my sister and her kids come out for the holidays, and I don’t want them to see cards signed with two girls’ names. We’d hear that someone’s mother or father had died back in Hibbing or Fergus Falls, but we didn’t send flowers or cards. We didn’t attend the funerals of the women who had never come out to their families, who thought, after twenty years or thirty-six years, it was always summer on the ball field and no one knew their vivid secret, which was right there for anyone to see anytime.

When the fire had burned to glowing coals and the dark crept closer, we’d pull out our sweaters and gather our crops and caulk our windows for winter; crows took up their demanding bleating. We ducked our heads and averted our eyes. The hungry ghosts were angry and hungry and they wanted to be fed.

Some years, a fiddle and guitar played. Couples two-stepped in the grass. The hungry ghosts opened their hungry mouths, rattling their dry bones, swallowing everything. All the women, lovers, circled the bonfire, swaying in the firelight, singing “Good Night Irene.” I’ll see you in my dreams.

Lynette D’Amico is an essayist and fiction writer whose work has appeared in the Gettysburg Review and the Ocean State Review and at Brevity, Slag Glass City, and Guernica. She holds an MFA from the Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. She makes her home in Rhode Island, but she has a prairie eye. Connect with her on Instagram.

This essay is a Short Reads original.

PS/ If you enjoyed this issue, please forward it to a pal. It only takes 26 seconds. This story took 26 years to be told.

Want more like this? Subscribe to Short Reads and get one fresh flash essay—for free—in your inbox every Wednesday.