The Process Server

by Jared Hanks | An unforgettable early morning delivery.

It’s early, still dark outside, as I pull into a nice neighborhood in my old Toyota pickup, the muddy all-terrain tires humming on the smooth road. I find the house. A shiny black BMW is backed into the driveway. It’s running, with the lights on—my client’s getaway car, I assume.

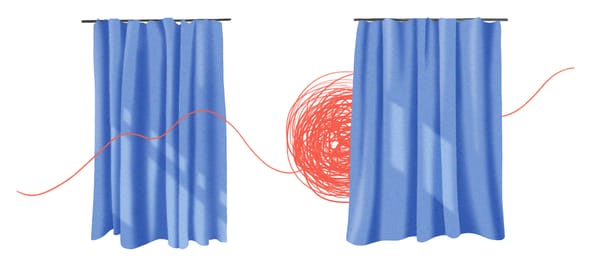

I am a process server. I hand deliver legal documents to people involved in court cases. I serve all kinds of papers: summonses and complaints, family court documents and subpoenas, and truckloads of divorce papers. Some people can’t get the divorce papers fast enough, while others evade them like the plague. My client’s wife does not want a divorce, and her parents forbid it. To further complicate the situation, her parents live in the same house as she and her husband do. My client is afraid that his father-in-law will do something crazy if he sees me serve his daughter the papers. So he has asked me to meet him at his house at five thirty in the morning, when he can assure easy service.

I get out of my truck and walk to the house.

He comes around the side of his car quickly, surprising me.

“Hey,” he whispers.

“I’m the process server,” I say.

“This way,” he whispers.

I don’t like this situation, but I haven’t liked a lot of the situations I’ve been in while doing this job. I’ve had a towering 350-pound professional football player yell at me on the steps of his mansion. I’ve had a crazy-eyed, tatted-up man threaten to shoot me with his Glock. I’ve maneuvered my way through a gang of leather-clad Hells Angels in a tiny biker bar way out in the boonies to serve a pissed-off DJ. It’s been pretty scary at times, but I have to do it: I have a two-year-old baby girl at home who’s got to eat.

So I trail my client to the front door. He pushes the door open, and then he steps back and motions me in. I don’t move. I just look at him. He’s dressed for work, wearing loafers, slacks, and a tucked-in button-up shirt. His black hair is gelled, his skin olive, his eyes dark and handsome.

Memorizing faces has become a habit in this job. I have to remember the face of each person I serve a legal document to, just in case I have to testify in court that the papers were received. Some process servers keep a journal, describing each person that they’ve served, but I don’t. When I’m not working as a process server, I’m a writer, and I have been using this job to fine-tune my ability to notice and remember details. I treat it like a memory exercise.

I have hundreds of faces etched in my mind. I once banged on an old, rotten trailer home way back in the woods, and a thin young woman answered the door. I took note of her curly hair and penciled-in eyebrows and a space like a corn kernel in the top row of her teeth. She took the papers and broke into a little dance. “I’m getting a divorce!” I could hear her screaming in joy as I walked back to my truck. Another time, I waited outside of a courthouse bathroom for a man I was trying to serve. He came out and glared at me. I took note of his angry blue eyes and the networks of veins in his cheeks and on his nose. I asked him his name. He turned away from me, and I took the folded divorce papers out of my back pocket and dropped them onto the floor, where they landed with a thud.

I don’t mind carrying these faces in my mind—she was beautiful and happy, and he was an angry jerk who probably deserved to be divorced—but there are other faces I wish I didn’t have to remember. Once, I served an old man who had to be in his nineties. He shuffled to the door, opened it, and stood in front me, his jaundiced skin dripping off his bones. His eyes were yellow, too. I gave him the papers. “Divorce!” he said, completely shocked.

“Are you OK, sir?”

“I’m so alone,” he said, as he shuffled back into his dark house. I walked back to my truck, got in, and called my wife. Fighting back tears, I told her that I loved her.

~~~

“Go, go,” my client whispers, gesturing toward his house.

“No,” I say. “You go first, and I’ll follow you.”

“But . . .”

“No,” I say. “I’ll follow you.”

He nods.

I follow him into the house. He tiptoes quickly down the long hallway, his loafers not making a sound while the hard soles of my Red Wing boots clip against the tile flooring, echoing throughout the big house. A door is open to a room at the end of the hallway. He turns and looks at me. He nods. I nod. He flips on the light.

“Samia,” he says.

I walk into the room. A bleary-eyed woman sits up in the bed. I don’t want to see the little girl sleeping by her; she has to be around the same age as my daughter.

“Are you Samia Said, ma’am?” I ask.

I study her face as I wait for an answer. Her long, dark hair is awry. She has high cheekbones. Her jawline is sharp but delicate. Above her right eyebrow, she has a small scar that reminds me of the small white scar that follows the contour of my wife’s Cupid’s bow.

“Yes,” she says, her dark eyes now welling with tears.

I commit her face to memory. But I don’t have to. I couldn’t forget it if I tried.

Jared Hanks is an MFA candidate at Savannah College of Art and Design. His work can be found in Rain Taxi Review of Books and Creative Nonfiction. He’s currently working on “Murdery: A Love Story,” a memoir about a research project gone very awry. He lives in Savannah, Georgia, with his wife and daughter.

This essay is a Short Reads original.

PS/ We’re looking for flash nonfiction reprints. See the submission call →